Diet has shaped human jaw bones; a result that could help explain why many people suffer with overcrowded teeth.

The study has shown that jaws grew shorter and broader as humans took on a more pastoral lifestyle.

Before this, developing mandibles were probably strengthened to give hunter-gatherers greater bite force.

The results were published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“This is a fascinating study which challenges the common perception that there has been little recent change in the morphology of humans,” said anthropologist Jay Stock from the University of Cambridge.

Many scientists have suggested that the range of skull shapes that exist within our species is the result of exposure to different climates, while others have argued that chance played more of a role in creating the diversity we see in people’s profiles.

The new data, collected from over 300 skulls, across 11 populations, shows that jaws shortened and widened as humans moved from hunting and gathering to a more sedentary way of life.

The link between jaw morphology and diet held true irrespective of where people came from in the world, explained anthropologist Noreen von Cramon-Taubadel from the University of Kent.

Concurrently crooked

It would be tempting to conclude that this is evidence for concurrent evolutionary change – where jaw bones have evolve to be shorter and broader multiple, independent times, she told BBC News.

But the sole author of the paper suggested that the changes in human skulls are more likely driven by the decreasing bite forces required to chew the processed foods eaten once humans switch to growing different types of cereals, milking and herding animals about 10,000 years ago.

“As you are growing up… the amount that you are chewing, and the pressure that your chewing muscles and bone [are] under, will affect the way that the lower jaw is growing,” explained Dr von Cramon-Taubadel.

She thinks that the shorter jaws of farmers meant that they have less space for their teeth relative to hunter-gatherers, whose jaws are longer.

Teeth-pulling tale

“I have had four of my pre-molars pulled and that is the only reason that my teeth fit in my mouth,” said Dr von Cramon-Taubadel.

Ever since that time, she has wondered why so many people suffer with teeth-crowding.

“I think that’s the reason why this result resonates with people,” she said.

Dr Stock added: “[The finding] is particularly important in that it demonstrates that variation that we find in the modern human skeletal system is not solely driven by population history and genetics.”

These results fit with previous evidence of both a reduction in tooth and body size as humans moved to a more pastoral way of life.

It also helps explain why studies of captive primates have shown that animals tend to have more problems with teeth misalignment than wild individuals.

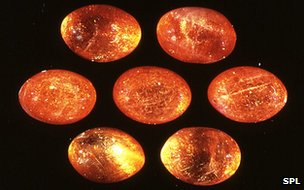

Further evidence comes from experimental studies that show that hyraxes – rotund, short-tailed rabbit-like creatures – have smaller jaws when fed on soft food compared to those fed on their normal diet.

:: Read original here ::