A new technique has been helping scientists piece together how the Earth’s continents were arranged 2.5 billion years ago.

The novel method allows scientists to recover rare minerals from rocks.

By analysing the composition of these minerals, researchers can precisely date ancient volcanic rocks for the first time.

By aligning rocks that have a similar age and orientation, the early landmasses can be pieced together.

This will aid the discovery of rocks rich in ore and oil deposits, say the scientists. The approach has already shown that Canada once bordered Zimbabwe, helping the mining industry identify new areas for exploration.

Dr Wouter Bleeker, from the Geological Survey of Canada, explained that much of the geology that exists today formed around 300 million years ago when the supercontinent Pangea existed.

“We really don’t understand the [Earth’s] history prior to Pangea,” he told a recent meeting of the American Geophysical Union in Toronto.

Early landmasses

Analysis of rocks that formed when continents drifted apart can help geologists reconstruct early landmasses.

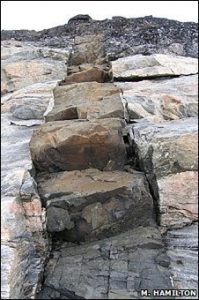

Dr Richard Ernst, a geologist from the University of Ottawa, explained that molten magma fills the cracks formed by shifting continental plates.

The magma cools to form long veins of basalt – a volcanic rock – that has a “distinct magnetic signature” revealing the rock’s orientation and latitude when it formed.

By combining this “magnetic signature” with the ages of these rocks, researchers can tell whether rocks on different continents were once part of the same volcanic up-welling.

But until now, researchers have been unable to determine the ages of many of these ancient rocks because of the difficulty in extracting the minerals used to date them.

“We are dealing with such small mineral crystals – typically much less than 100 microns long – we are talking about grains far smaller than the width of a human hair,” explained Dr Michael Hamilton, a geologist and co-leader on the project.

But with the development of new techniques, minerals – such as baddeleyite – can now be successfully recovered.

Baddeleyite is useful because it incorporates large amounts of uranium into its crystal-structure, and because uranium naturally decays to lead. Scientists also know the rate at which this happens.

“[They] can use these minerals as radioactive clocks,” Dr Hamilton added.

“All we need to do is measure the the amounts of uranium and lead very precisely.”

In a large, international project, researchers hope to collect and date 250 rocks from around the world, and use this information to reconstruct how these continental fragments were once together to form giant landmasses that existed 2.5 billion years ago.

:: Read original here ::

Formic acid, a molecule implicated in the origins of life, has been found at record levels on a meteorite that fell into a Canadian lake in 2000.

Formic acid, a molecule implicated in the origins of life, has been found at record levels on a meteorite that fell into a Canadian lake in 2000. The smallest meat-eating dinosaur yet to be found in North America has been identified from six tiny pelvic bones.

The smallest meat-eating dinosaur yet to be found in North America has been identified from six tiny pelvic bones.

The world’s largest catalogue of Beatles-related recollections will be unveiled in Liverpool this week.

The world’s largest catalogue of Beatles-related recollections will be unveiled in Liverpool this week.