Stop it! Don’t touch that! Sit down and be quiet! Whether you heeded these commands as a child could help predict your future. A new study suggests that people who show less self-control as young children are more likely to have failing health, greater debt, and run-ins with the law later in life.

Stop it! Don’t touch that! Sit down and be quiet! Whether you heeded these commands as a child could help predict your future. A new study suggests that people who show less self-control as young children are more likely to have failing health, greater debt, and run-ins with the law later in life.

The idea that willpower is important for success is not new. In the late 1960s, Walter Mischel, a psychologist at Columbia University, tested whether 4-year-old children could resist nibbling Oreo cookies when left alone with a plate of them. He and colleagues found a huge range in willpower, and those children better at resisting the temptation went on to do better in school, scoring higher on the standardized tests. Their parents also judged them to be more attentive, competent, and intelligent. Intrigued, psychologist Terrie Moffitt of Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, and her colleagues sought real-life data to test whether individuals with more willpower and not just self-discipline when offered cookies, achieved greater success in life.

The international team tracked approximately 1000 New Zealand children, born in 1972 or 1973, from the age of 3 years until their early 30s, and another 500 British fraternal twins, born in 1994 or 1995, from the ages of 4 years to 12 years. They used a range of measures to assess the children’s self-control, including their impulsivity, persistence at a task, patience while waiting in line, and hyperactivity.

Compared with their more disciplined twins, children who had less self-control at age 5 were more likely to have begun smoking, performing badly in school, and acting out at age 12, the researchers report online today in the Proceedings of National Academy of Sciences. And these problems continued in later life. Controlling for socioeconomic status and IQ, the researchers determined that people who showed the lowest willpower as children went on to be more than twice as likely to have health problems in their 30s, including high blood pressure, weight problems, lung disease, and sexually transmitted diseases. By the age of 32, they also earned 20% less and were about three times more likely to be dependent on tobacco, alcohol, or harder drugs and to have been convicted of a crime.

Moffitt explains that people didn’t fall into two categories—disciplined or undisciplined—but existed on a spectrum. “It means all of us could benefit from improving our self-control,” she says.

Moshe Bar, a psychologist at Harvard Medical School in Boston who was not involved in the study, is impressed by the long-term data set but cautions that the study is observational and can’t establish that self-control breeds success. Still, parents of cookie nibblers shouldn’t despair, he says. He was intrigued to read that some of the children in the study improved their self-control. Bar and his 7- and 10-year-old children “play a game of ‘waiting’ with unwrapping a candy for no other reason than practicing a delay,” he says. “It works,” he says, but then, as he points out, he has a sample size of only two.

:: Read full here ::

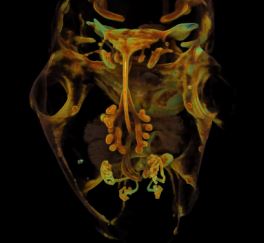

If you ever wanted to know how the inner organs of a mouse embryo form, this is the movie for you. The animation was created by imaging thin sections of an embryo and then stacking these images to make a 3D movie. “If you look closely, you can see the developing lungs, gut, kidney, and bladder,” says the movie’s creator, Ian Smyth, a developmental biologist at Monash University in Australia. His video was selected from among several for being the most “striking and technically excellent” of the animations submitted to this year’s Wellcome Image Awards in London. Smyth uses these animations to compare normal tissues in embryos with those whose development is disrupted because of disease or exposure to a toxin. The animation was selected because of its ability to illustrate how effective this imaging technique can be for looking at the internal structure of the organs in a noninvasive way, explains Catherine Draycott, one of this year’s judges. “You can almost travel through [the mouse] as it develops.”

If you ever wanted to know how the inner organs of a mouse embryo form, this is the movie for you. The animation was created by imaging thin sections of an embryo and then stacking these images to make a 3D movie. “If you look closely, you can see the developing lungs, gut, kidney, and bladder,” says the movie’s creator, Ian Smyth, a developmental biologist at Monash University in Australia. His video was selected from among several for being the most “striking and technically excellent” of the animations submitted to this year’s Wellcome Image Awards in London. Smyth uses these animations to compare normal tissues in embryos with those whose development is disrupted because of disease or exposure to a toxin. The animation was selected because of its ability to illustrate how effective this imaging technique can be for looking at the internal structure of the organs in a noninvasive way, explains Catherine Draycott, one of this year’s judges. “You can almost travel through [the mouse] as it develops.”