Astronomers have spied a star’s swan song as it is shredded by a black hole.

Astronomers have spied a star’s swan song as it is shredded by a black hole.

Researchers suspect that the star wandered too close to the black hole and got sucked in by the huge gravitational forces.

The star’s final moments sent a flash of radiation hurtling towards Earth.

The energy burst is still visible by telescope more than two-and-a-half months later, the researchers report in the journal Science.

The Swift spacecraft constantly scans the skies for bursts of radiation, notifying astronomers when it locates a potential flare.

These bursts usually indicate the implosion of an ageing star, which produces a single, quick blast of energy.

But this event, first spotted on 28 March 2011 and designated Sw 1644+57, does not have the marks of an imploding sun.

What intrigued the researchers about this gamma ray burst is that it flared up four times over a period of four hours.

Astrophysicist Dr Andrew Levan from the University of Warwick, and his colleagues suspected that they were looking at a very different sort of galactic event; one where a passing star got sucked into a black hole.

The energy bursts matched nicely with what you might expect when you “throw a star into a black hole”, Dr Levan told BBC News.

Gasless centres

Black holes are thought to reside at the centres of most major galaxies. Some black holes are surrounded by matter in the form of gas; light is emitted when the gas is dragged into the hole. However, the centres of most galaxies are devoid of gas and so are invisible from Earth.

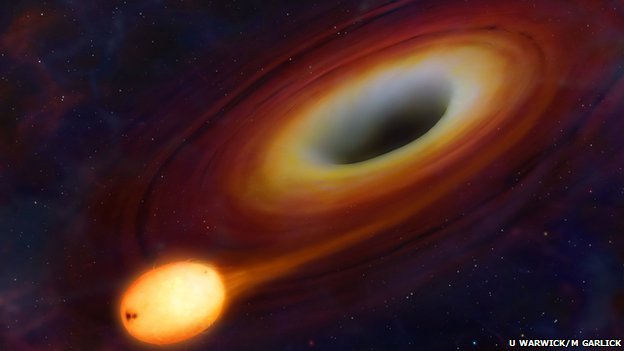

These black holes only become visible when an object such as a star is pulled in. If this happens, the star becomes elongated, first spreading out to form a “banana shape” before its inner edge – orbiting faster than the outer edge – pulls the star into a disc-shape that wraps itself around the hole.

As material drops into the black hole it becomes compressed and releases radiation that is usually visible from Earth for a month or so.

Events like these, termed mini-quasars, are incredibly rare – researchers expect one every hundred million years in any one galaxy.

The researchers used some of most powerful ground-based and space-based observatories – the Hubble Space Telescope, the Chandra X-ray Observatory and the Gemini and Keck Telescopes.

:: Read original here ::